WHERE ARE WE NOW?

A Look Back and a Look Forward at 60 Years of Penn Lines

Jill Ercolino

Editor

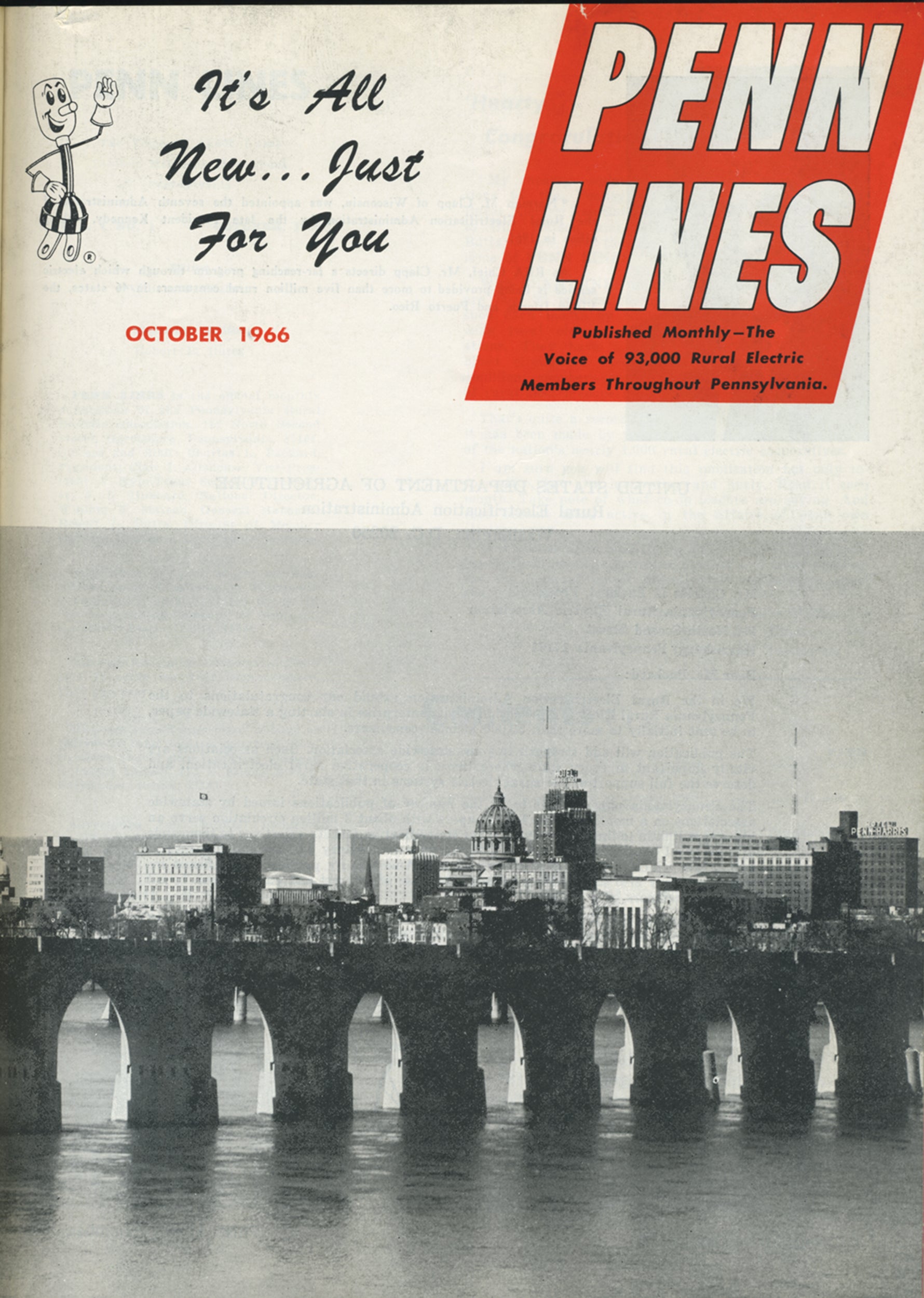

When Penn Lines debuted in October 1966, rural Pennsylvania was already electrified, but the cooperative story was still being written – much like it is today. And as rural electric cooperatives have evolved, so has their monthly magazine.

Some things, however, haven’t really changed at all. In fact, that very first issue, despite its age, has set the tone for every Penn Lines since.

“The point was never to talk at cooperative members – it was to talk to them,” says Steve Brame, president & CEO of the Pennsylvania Rural Electric Association (PREA) and Allegheny Electric Cooperative, Inc. (Allegheny) “Since the beginning, we’ve been focused on giving consumers the information they need to understand what’s happening with their power and why.”

And it’s that simple, no-frills mission that has carried Penn Lines forward for six decades.

October 1966: Penn Lines debuts as the official magazine of the Pennsylvania Rural Electric Association.

Building trust

The design of the first Penn Lines echoed its straightforward messaging. More like a newsletter than a magazine, it leaned toward a practical tone and feel.

Inside were congratulatory messages from leaders who understood the promise and responsibility of rural electrification, including Gov. William Scranton; Dr. Leland H. Bull of the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association (NRECA); Clyde Ellis, general manager of the Rural Electrification Administration; and PREA President Charles Packard of Valley Rural Electric Cooperative (REC).

Their remarks underscored a shared belief that strong electric cooperatives depend on informed members.

“That understanding has never gone away,” Brame says. “Communication is not a side function for cooperatives — it’s central to how the model works. Penn Lines became one of the ways that trust was built and sustained.”

Beyond those messages, the magazine grounded its mission in everyday cooperative life. Readers found updates from local cooperatives, statewide news about power and policy, and coverage tied to familiar community events. One early photograph showed Somerset REC Manager D.W. Smith presenting the local fair queen with a Willie Wiredhand doll — a small moment that captured the magazine’s larger intent of reflecting the communities that cooperatives serve.

Early issues devoted significant space to local cooperative news — the information members cared about most — while also explaining broader issues like energy use, rates and costs, and political action. Lifestyle content also graced the pages. In November 1966, Penn Lines introduced a recipe column, known as “Woman to Woman.” Today, it’s called “Cooperative Kitchen” and remains one of the magazine’s most popular features.

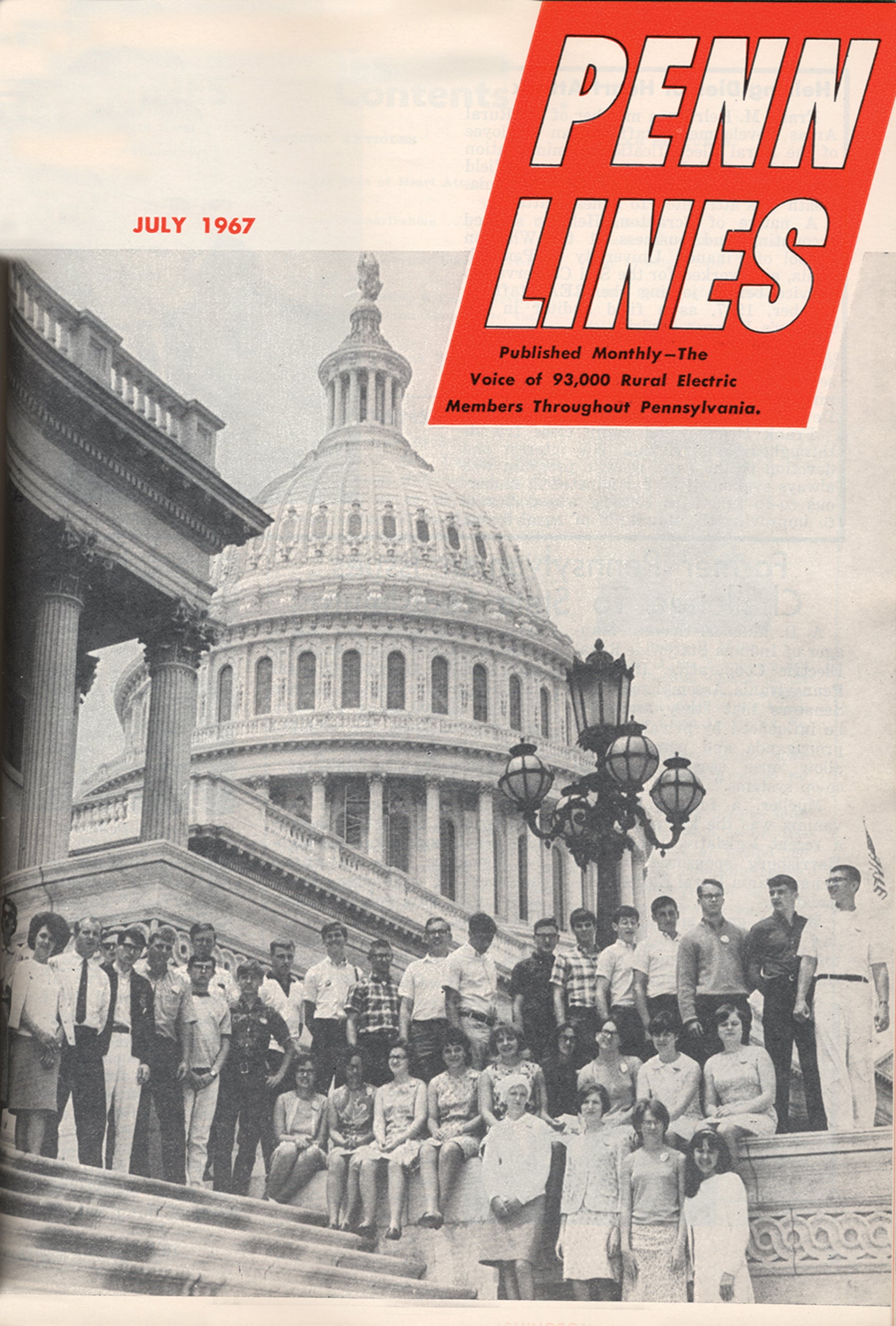

Coverage of youth and education followed soon after. In 1967, Penn Lines began covering the Rural Electric Youth Tour in Washington, D.C., by spotlighting local cooperative students on the steps of the U.S. Capitol and reinforcing the cooperative commitment to leadership development. Photos of scholarship recipients began appearing in print not long after, another tradition that continues today.

November 1966: The magazine introduces its first recipe column, "Woman to Woman" — now "Cooperative Kitchen," one of Penn Lines’ most popular features.

Politics and power

By the late 1960s, Penn Lines was also documenting the political realities facing electric cooperatives.

In April 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson — himself a former electric cooperative director — appeared on the magazine’s cover in a photo taken during the NRECA Annual Meeting in Dallas, Texas. Coverage focused on issues like territorial integrity and access to power, themes that resonated with cooperative members.

That same year, Penn Lines published a special edition responding to private power company encroachment into cooperative territories and encouraging support for the Electric Consumer Protection Act. The issue laid out the stakes, reinforcing the magazine’s mission of explaining issues that directly affected cooperative stability.

“Penn Lines has always had a steady voice,” Brame says. “It doesn’t chase headlines. It explains what’s happening, why it matters to cooperative members, and how it connects back to their communities.”

As cooperatives strengthened their infrastructure, Penn Lines followed those developments closely, too.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the magazine tracked escalating energy costs, federal funding debates and the pursuit of long-term, reliable generation. It reported extensively on the development of the Susquehanna Steam Electric Station, from the early planning to the construction and commercial operation of the Luzerne County nuclear plant. This project was pivotal, marking the first time Pennsylvania and New Jersey cooperatives owned a share of their power supply.

Penn Lines also chronicled Allegheny’s decades-long exploration of small hydroelectric projects, culminating in the construction of the plant at Raystown Dam, which came on-line in 1988. Another cooperative-owned power source, Raystown, like Susquehanna, continues to provide clean energy today.

On the load-management front, articles explained how coordinated systems shifted electric use away from peak hours, an initiative that brought cooperatives and consumers together to manage costs and maintain reliability.

“Our job has always been to connect the dots,” says Pete Fitzgerald, PREA/Allegheny vice president - public affairs & member services and executive editor of Penn Lines. “We explain what’s being built or changed, but more importantly, we explain why it matters to a member sitting at their kitchen table.”

1970s: The magazine tracks rising energy costs, fuel concerns and the growing importance of long-term power planning for cooperatives.

The heart of the magazine

One reason Penn Lines has endured is that it has never been produced in isolation.

“Every issue begins with listening,” Fitzgerald says. “Local cooperatives tell us what their members are asking about, what’s changing on the ground and what stories need to be told. The magazine is built from that collaboration.”

And as rural Pennsylvania evolved, Penn Lines has widened its lens — adding more photography, longer features and stories about travel, food, outdoor recreation and local history — while keeping cooperative education at its core.

“Local cooperatives have always been co-creators of the magazine; we call them the heart of the publication because their stories take center stage – right in the middle of the magazine,” Fitzgerald adds. “That’s intentional and that’s how we make sure Penn Lines stays relevant month after month, community by community.”

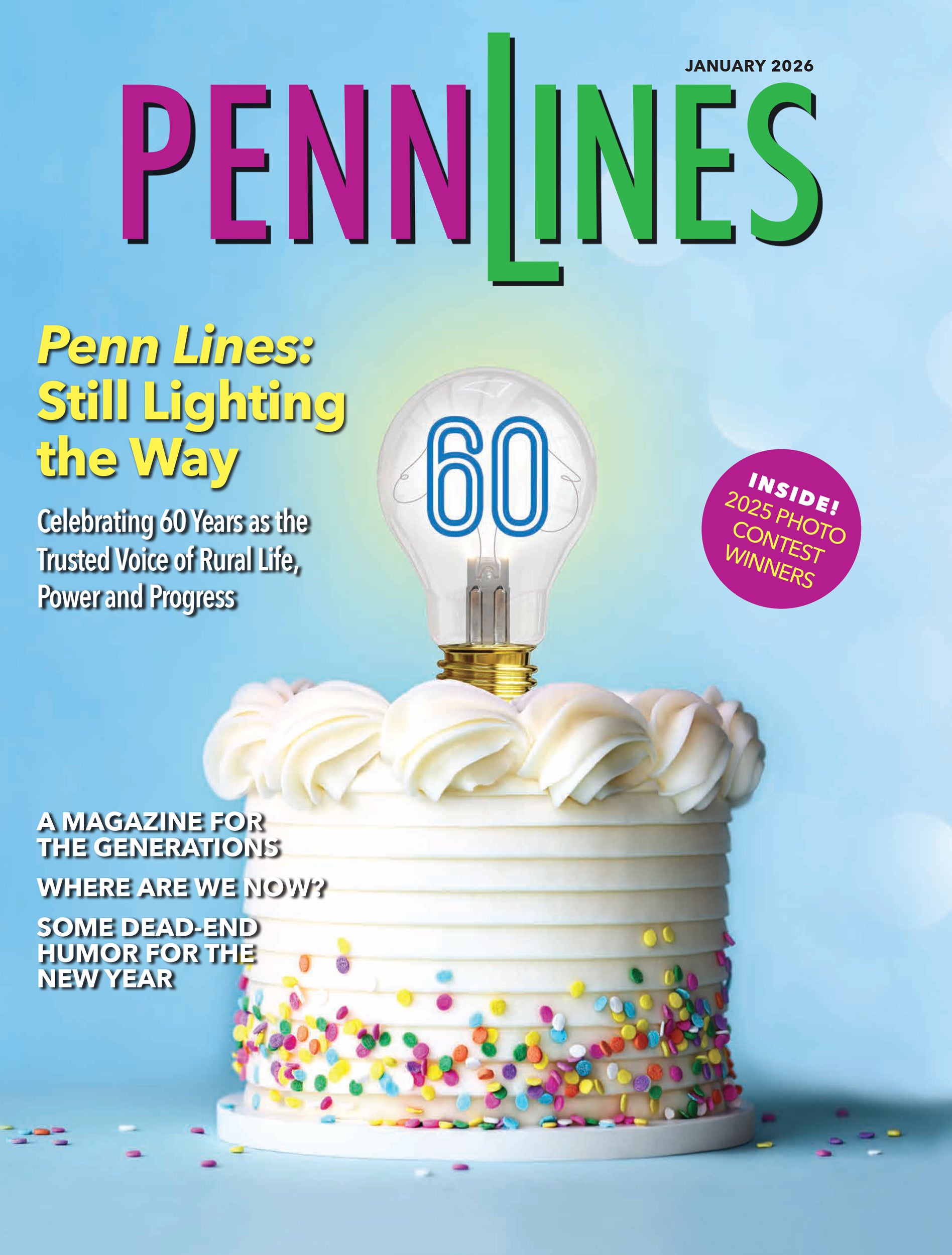

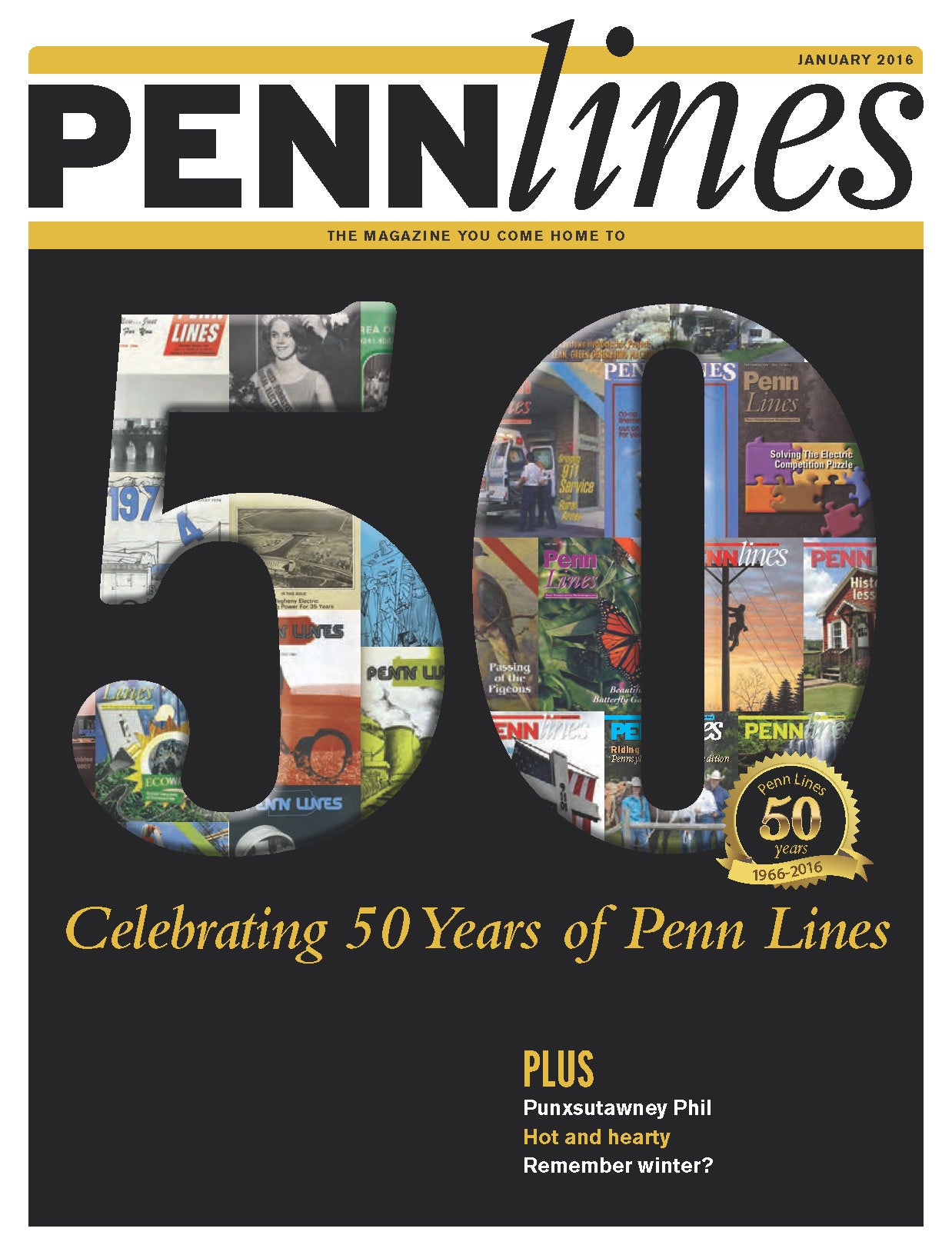

By the time Penn Lines marked its 50th anniversary in 2016, it had become a constant in cooperative households. That loyalty has only deepened. A 2025 readership study found that four out of five respondents are regular readers, with nearly three-quarters reading every issue. Two out of five have been reading Penn Lines for more than 20 years.

“Longevity alone doesn’t explain that kind of loyalty,” Fitzgerald says. “What explains it is credibility. Penn Lines has stayed focused on facts and local impact — even when the topics were complicated or uncomfortable.”

1980s: Penn Lines features extensive coverage of cooperative power-supply milestones, including the development of the Susquehanna Steam Electric Station, a nuclear power plant in Luzerne County, and the hydroelectric plant at Raystown Dam. Together, these plants continue to provide most of the power distributed to Pennsylvania and New Jersey cooperatives.

Staying grounded

As Penn Lines celebrates its 60th anniversary, the energy environment is more complex than at any point in the magazine’s history. Reliability pressures are intensifying. Infrastructure costs are rising. Policy debates are louder. Members face more information — and misinformation — than ever before.

“The stakes are higher now,” Brame says. “That makes the magazine’s role even more important. Members need a source they can rely on — not for spin, but for clear, grounded information.”

2000s: Penn Lines goes through a series of redesigns, including one to mark its 50th anniversary in 2016. The most recent redesign was introduced in 2022.