BIG DEMANDS

BIG QUESTIONS

What Data Centers Mean for Communities and the Grid

By Michael T. Crawford

Senior Technical Editor

TREMENDOUS DEMAND: Hyperscale data centers like this one can use as much electricity as a small city.

For nearly 60 years, the Homer City Generating Station in Indiana County was a coal-burning, energy-producing powerhouse. In its heyday, the plant — the largest of its kind in Pennsylvania — employed thousands and supplied millions with electricity.

By the mid- 2000s, however, natural gas began overtaking coal as the primary source for electric generation in the U.S., a movement driven by the shale gas boom. Ironically, Indiana County — like much of western Pennsylvania — sits atop the vast, energy-rich Marcellus Shale, which since its uncovering two decades ago, has turned the Commonwealth into a major natural gas producer, second only to Texas.

While the growth of natural gas generation eventually led to the closure of Homer City’s coal plant in 2023 and its recent demolition, it has just as quickly led to the site’s rebirth. Today, a new natural gas complex, the proposed $10 billion Homer City Energy Campus, is taking its place to electrify another kind of powerhouse — the 21st-century, technological kind: massive data centers.

Now, as one energy chapter closes and another, much different one begins in this pocket of Pennsylvania, the project has raised broader questions about the impact of data centers on host communities, surrounding regions and Pennsylvania as a whole.

“What’s happening at Homer City is bigger than one project,” says Steve Brame, president & CEO of the Pennsylvania Rural Electric Association (PREA) and Allegheny Electric Cooperative, Inc. (Allegheny), which represent the 14 rural electric cooperatives in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. “It reflects how our energy story keeps evolving — and why it’s so important to understand not just what’s being built, but how it fits into our communities, our grid, and our long-term energy needs.”

A NEW CHAPTER: The Homer City coal plant was once a powerful resource for electricity in western Pennsylvania. Today, the site below has been cleared to make room for a multi-billion-dollar natural gas facility that will energize multiple hyperscale data centers. Photo courtesy of Ruben A. Campos, helicopter pilot

Welcome to the future

Some, including Gov. Josh Shapiro, are welcoming data centers as job creators and economic drivers and dumping billions into their development. Last year, for instance, at the inaugural Pennsylvania Energy and Innovation Summit in Pittsburgh, President Donald Trump and U.S. Sen. Dave McCormick (R) announced the Commonwealth would be receiving more than $90 billion in private investments to build data centers and power plants to support them.

Others have been more cautious, raising concerns about grid reliability (large data centers use as much electricity as a small city), the environment and increasing electric rates.

“Data centers are really driving the conversation in the energy sector and beyond,” says Matt Leonard, PREA/Allegheny manager of government & regulatory affairs. “There is real increased demand on the energy grid coming from the construction and operation of these data centers, and it’s impacting all Pennsylvanians. That’s true whether you’re a consumer-member of an electric cooperative or a customer of any other power provider in the Commonwealth.”

When it opens — 2027 is the target date — the reborn Homer City site will house the nation’s largest natural gas-powered plant, which will energize multiple, 500-megawatt (MW) data centers. The campus is located in a rural area neighboring territory served by REA Energy Cooperative.

REA’s President & CEO Chad Carrick, who also serves as treasurer of the Indiana County Chamber of Commerce, sees the potential of the project, which is expected to create thousands of jobs and bump up local tax revenues.

FEEDING A NEED: Packed tight with servers and computer processors, data centers power the systems behind emails, video streaming, online banking, cloud-based storage, social media — and even your cooperative’s coordinated load management system.

“There are a lot of positives,” he says. “This is an area that’s lost population throughout the years, and when you lose population, you lose your tax base. So when the Homer City power plant shut down, that was a tax base that went away. Now that’s coming back — and then some.”

In Loudoun County, Virginia — more often referred to as Data Center Alley because of its high concentration of data centers (around 199, with 117 more planned) — the facilities generate nearly half of the county’s property tax revenue, according to the county’s website.

Since 2008, data centers have reduced the county’s property tax rate by more than 37% and added $26 in tax revenue for every $1 in services they use. Land value has also surged to more than $2.1 million per acre.

The evolution of data centers

As for Pennsylvania, at least one research organization has said it’s “quickly emerging” as a major hub for gas-powered data centers, with more than two dozen currently looking to call the Commonwealth home.

At its most basic level, a data center is a building that holds large-scale computers. The first — the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer — was developed in 1945 at the University of Pennsylvania so the U.S. Army could compute firing tables for artillery. It occupied 300 square feet and used about as much energy as 125 homes.

Data centers, as we know them, took off during the dot-com era in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and they’ve continued to grow as internet-connected devices have become more commonplace. They power the systems that make emails, video streaming services, online banking, cloud-based storage, social media and even your cooperative’s coordinated load management system possible.

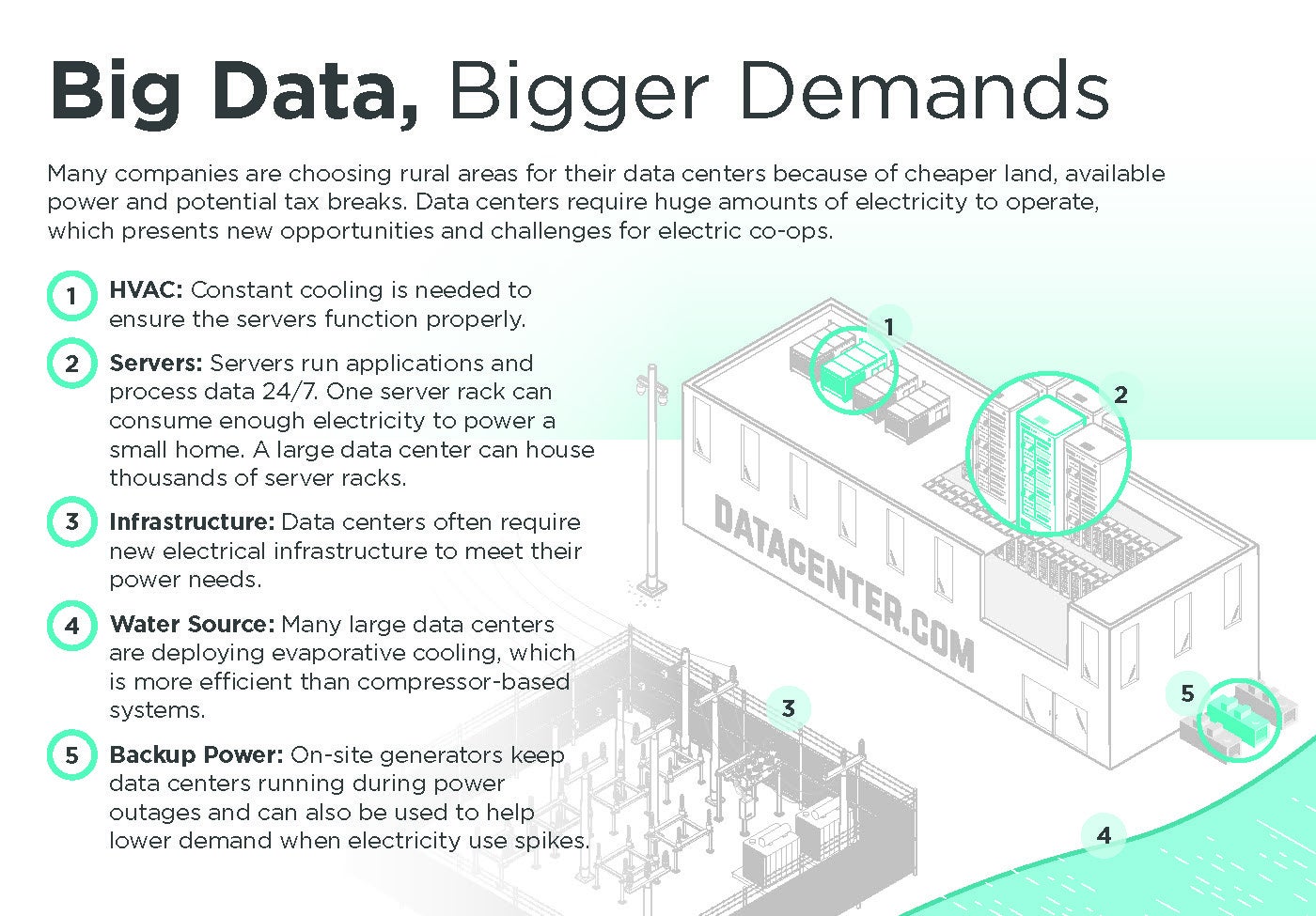

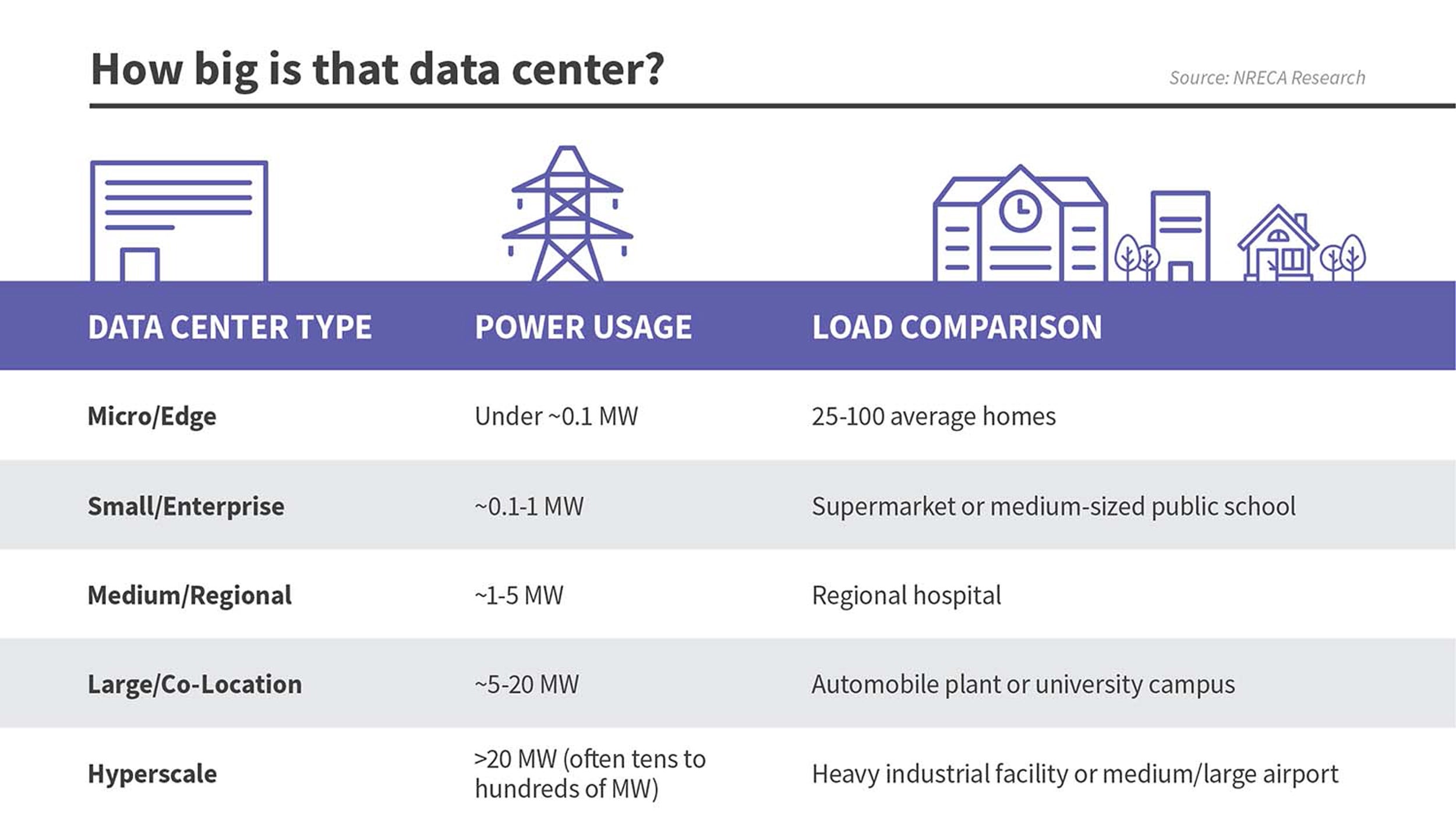

Courtesy of the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association

Today, a single data center can occupy hundreds of thousands of square feet and use more energy than all of Pittsburgh. These hyperscale buildings are generally warehouses packed tight with computer processors powering artificial intelligence (AI). One study found that when someone poses a question to an AI platform — popular ones include ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini and Claude — it requires about 10 times more electricity than a Google search.

Needless to say, their hunger for power has grabbed the energy industry’s attention and increased worries that their large loads and constant demand will overwhelm the grid. Continued rate spikes are another concern.

Last December, PJM Interconnection, the regional grid operator for Pennsylvania and 12 other states, projected electricity demand will grow by 32 gigawatts (GW) by 2030, with nearly 30 GW of that driven by data centers.

“We’ve spent a considerable amount of time preparing for the growth of data centers,” Brame says. “That includes planning for how they will impact the grid and how to manage those that may eventually want to connect to a local electric cooperative.”

Consumers, cooperatives weigh in

Steve Allabaugh, president & CEO of Wysox-based Claverack Rural Electric Cooperative (REC), says getting involved at a project’s ground level is key.

Like their neighboring cooperative, Mansfield-based Tri-County REC, Claverack has invested in bringing fiber-based broadband internet to the region, something data centers require to reach end-users. However, significant infrastructure development — and lots of analysis — would still be required if any hyperscale data centers, defined as those requiring 100 to 300 MWs of around-the-clock electricity, were proposed in Claverack’s service territory, he says.

UNDER CONSTRUCTION: Amazon’s Luzerne County data center project, currently under construction, will be powered by the nearby Susquehanna Steam Electric Station, shown here. Through Allegheny Electric Cooperative, Inc., cooperatives in Pennsylvania and New Jersey own a 10% share of the nuclear power facility — a share that is dedicated strictly to co-op needs.

“The electrical demand of a big data center is multiple orders of magnitude larger than what a typical distribution system is designed to handle,” Allabaugh says. “Our local distribution substations have the capacity to support a big data ‘closet,’ not a data center.

“So if we were approached about a data center here,” he adds, “we would have to conduct an extensive engineering study and work closely with Allegheny, our generation and transmission provider, to ensure we could safely and reliably secure the power needed to support such a request.”

Still, the economic benefits may not be enough to justify the cost for some communities.

Aaron Young, president & co-CEO for Tri-County REC, says residents raised concerns about data centers at a recent meeting in Tioga County, which is part of the cooperative’s service territory.

“Obviously, there’s the potential impact on the grid, but without an engineering study, there are still a lot of unknowns,” Young says. “Our experience deploying fiber broadband taught us the importance of planning for infrastructure and community needs.”

In addition to electricity, data centers also rely on specialized computer components that generate intense heat, requiring robust cooling systems to keep operations stable. Those systems often depend on a continuous water supply — sometimes millions of gallons per day — which raises questions about sustainability and resource allocation in rural communities.

“Beyond infrastructure, residents have expressed broader concerns about how large-scale projects could affect local resources, quality of life, and short- and long-term planning,” Young says. “These conversations underscore the importance of transparency and collaboration as utilities and developers collaborate and weigh the benefits against potential community impacts.”

Courtesy of the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association

‘Our members are first and foremost’

Meanwhile, in Luzerne County, Amazon has been constructing a 300-MW data center right outside the Susquehanna Steam Electric Station, a nuclear power plant that provides Pennsylvania and New Jersey cooperatives with more than half of their energy. The plan there is similar to the one in Homer City: directly connect the data center to a 24/7 power plant to minimize the possibility of disruption.

Through Allegheny, cooperatives own a 10% share of the plant, a stake they don’t share with any other users.

“Our 10% is for our members,” says Todd Sallade, PREA/Allegheny vice president — power supply & engineering, “and it won’t go to large loads or new data centers.

“We have a responsibility to our members to ensure they’re not subsidizing the build-out of these projects,” he adds, noting it’s important that cooperatives not only work with developers but also hold them accountable. “There has to be a plan to ensure the money will be there, and our members aren’t left holding the bag if things don’t pan out.”

Back in Indiana County, REA Energy is doing just that, designing rate and cost-share systems to ensure that whatever happens in Homer City, it’s not at the expense of the co-op’s consumer-members.

“We want to make sure,” Carrick says, “that our members are first and foremost.”